Images from Beyond

Human interest in life beyond earthly existence has been a constant theme in human artistic expression from cave paintings to cathedrals to websites. There are many pictorial representations of heaven, where God often appears, in the Christian tradition. However, images of God are considered idolatrous in Judaism and Islam, and pictures of heaven are rare. In addition, Christian works of art are more readily available to Westerners than those representing Hindu or Buddhist ideas of heaven.

The works that appear in black and white in Beyond, or similar pieces in the public domain, are collected here in color. Also included are works of art that represent a figure or story referred to in the text. If you click on the image you can view a larger version, and if you want to refer to the book, page numbers for illustrations and further descriptions are included.

Shaman image from Lascaux. An Ice-Age depiction of a wounded bison and a man who may be a shaman who makes contact with life beyond while in a trance. (22-23)

Depiction of the Egyptian Field of Reeds from the Papyrus of Ani. A scene from the afterlife in A’aru, the Field of Reeds, a perfected reflection of life on earth. (33)

Adapa (1908) by Odilon Redon (1840-1916), Kroller-Muller Museum. Redon’s rendition of Adapa, a Sumerian otherworldly traveler, being caught up by the wind.

Ezekiel’s Chariot Vision by Matthaeus Merian (1593-1650). Ezekiel’s vision of heaven from the Old Testament, an inspiration to Jewish mystics for centuries. (55-56)

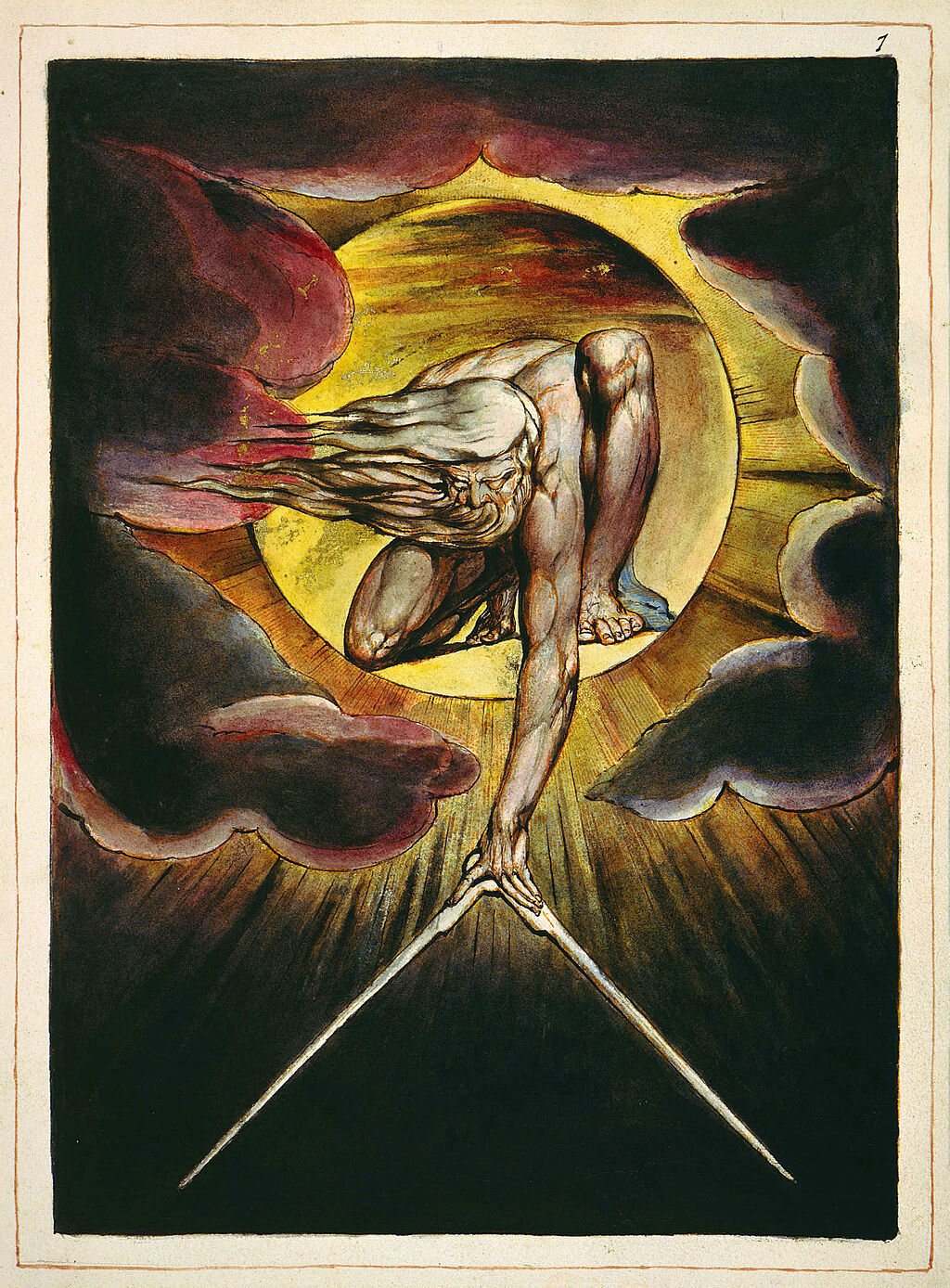

The Ancient of Days (1794) by William Blake (1757-1827). The visionary Blake’s rendition of the Ancient of Days, who ruled in favor of the Holy Ones in the Book of Daniel. (57)

Heaven scene in apse in Santa Pudenziana, Rome (4th-5th Century). Christ in heaven with his apostles, who invite us into their sacred space. (108-109)

Benson Madonna (c1475) by Antonello da Messina (1440-1479), National Gallery of Art. An intimate, playful portrait of the Mary and the infant Jesus. (125)

Enthroned Madonna and Child (c1250-75), National Gallery of Art. A regal Byzantine depiction of Mary and the infant Jesus. (125-26)

Mary, Queen of Heaven by the Master of the Saint Lucy Legend (c1485-1509), National Gallery of Art. Mary, mother of Jesus, surrounded by angels in the heavens beneath the Holy Trinity. (125-126)

Depiction of the Cosmos from The Nuremberg Chronicle. A delightful diagram of the cosmos as those in Dante’s time might have envisioned it. (126)

Dante’s Paradiso by Gustav Dore (mid 19th Century). One of a series of engraved illustrations of The Divine Comedy, in which Dante and his guide Beatrice gaze at the heavenly host in the shape of a rose. (130-131)

School of Athens (1509-1511) by Raphael (1483-1520), Apostolic Palace, Vatican. A vision of heaven celebrating human knowledge, inspired by classical ideals. (133-34)

Disputation of the Holy Sacrament (1509-1510) by Raphael (1483-1520), Apostolic Palace, Vatican). A Christian vision of heaven inspired by Raphael’s own faith. (133-34)

The Last Judgement (1306) by Giotto di Bondone (d. 1337), Scrovegni Chapel, Padua. Giotto’s heaven, where its inhabitants are ranked, absorbed in the beatific vision of God. (135)

The Last Judgment (1534-1541) (Sistine Chapel, Vatican) by Michelangelo (1475-1564). Christ as a terrifying judge, condemning the evil and summoning the good to heaven. (136-37)

Small Last Judgement (1619) by Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640). Beneath Christ on high, a swirl of bodies thought by some contemporaries to be scandalous. (140)

The Burial of Count Orgaz (1586-66) (Church of S. Tomé, Toledo) by El Greco (1541-1614). The soul of Count Orgaz makes its way from earthly to heavenly existence. (141-42)

Apotheosis of Saint Ignatius (1685) (Church of San Ignacio, Rome) by Andrea Pozzo (1642-1709). The boundary between earth and heaven disappears as St. Ignatius ascends to his heavenly reward. (143-44)

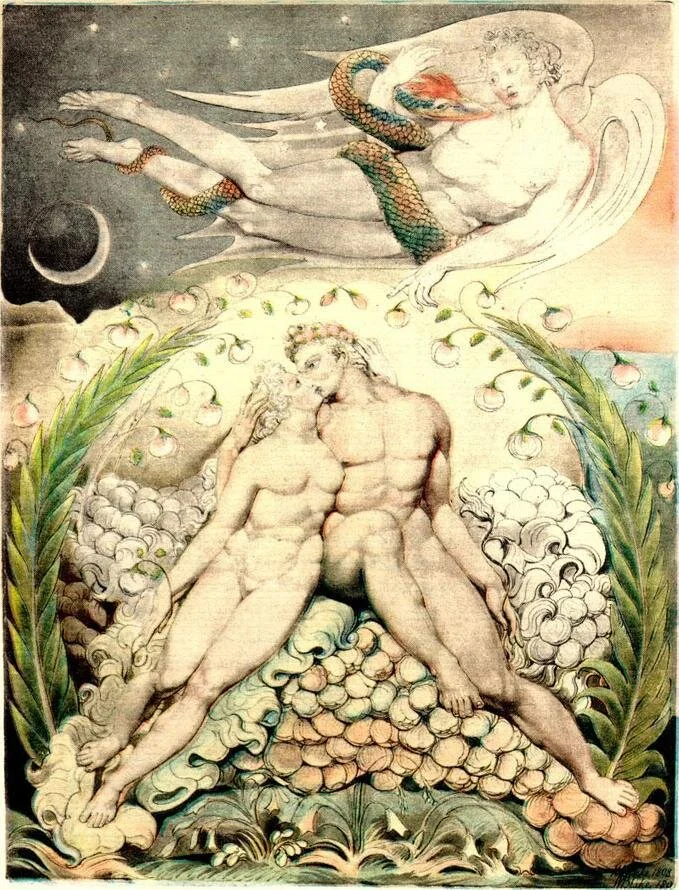

Satan Watching the Caresses of Adam and Eve (1808) by William Blake (1757-1827). A scene from Milton’s Paradise Lost wherein Satan watches with envy the lovemaking of Adam and Eve. (146)

Yama, Hindu God of Death (17th-early 18th Century) from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A frightening depiction of the powerful god of death and ultimate judge of souls. (213)

Hungry Ghosts Scroll (late 12th Century) from the Kyoto National Museum. A scene from the Buddhist underworld of hungry ghosts, who are consumed by greed. (228)

World Womb Mandala (early 17th Century) from Art Gallery of South Australia. A mandala showing Buddha surrounded by deities and bodhisattvas. (226-27)

Wheel of Existence (c1800) from Birmingham Museum of Art. Scenes from the afterlife within the body of Yama, Buddhist God of Death. (229)

Amitabha in Sukhavati Paradise from San Antonio Museum. Many Buddhists aspire to join Amitabha, Infinite Light, in his heavenly Pure Land. (235)

Goddess Kurukulla (Tara) (early 12th Century) from The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Tara, who reigns over the Pure Realm of Yulokod, is revered by Tibetan Buddhists. (241)

Paradise: Ascension into the Empyrean (c 1500-04) (Galleria dell-Accademia Venezia) by Hieronymus Bosch (c1450-1516). Souls journeying towards the ultimate light , the hope of many religious traditions. (276)

Portal (Alviso, California,2018) by Nora Cain. A doorway beyond.

The artworks included here are all from Wikimedia Commons, and are in the public domain. With a few exceptions, the Wikimedia Commons tagline for each of the artworks is:

Exceptions:

Shaman image from Lascaux:

Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled GNU Free Documentation License.

Goddess Kurukulla (Tara)

The person who associated a work with this deed has dedicated the work to the public domain by waiving all of their rights to the work worldwide under copyright law, including all related and neighboring rights, to the extent allowed by law. You can copy, modify, distribute and perform the work, even for commercial purposes, all without asking permission.